- Home

- Helen Peters

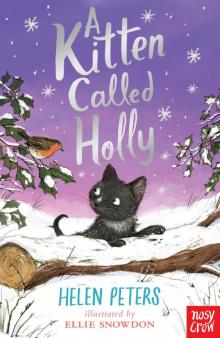

A Kitten Called Holly

A Kitten Called Holly Read online

Toffee sprang out of the Christmas tree, knocking over Mum’s vase of flowers. The water spilled on to Holly and Ivy. The drenched kittens howled in shock and started running madly around the room. The door opened and Dad appeared, holding a bunch of carrots. “What on earth is going on?” he shouted.

For Jimmy, Patrick and Megan

H. P.

For my sister, Lizzie

E. S.

“This is perfect,” said Jasmine, smiling at her best friend, Tom. “Come in, Sky, and don’t make a sound. We have to keep it secret from Manu.”

Jasmine’s collie dog, Sky, wagged his tail and padded into the shed. Jasmine pulled the door shut. It was coming off its hinges and the rotting wood dragged along the ground. It clearly hadn’t been shut properly for years.

“Sit, Sky,” said Jasmine, and Sky obediently sat on the dusty floor.

“I can’t believe we’ve never been in here before,” said Tom. “It will be really cosy when we’ve cleaned it up. Look, it’s even got a window.”

“We can bring out some old chairs,” said Jasmine, “and find something for a table. And we can clear all the junk out.”

The shed was a small brick building with a sloping roof, in the garden of the farmhouse where Jasmine lived. Two rusting oil stoves stood in one corner, next to a tangled bundle of wire and a collapsed straw bale. On a rough wooden shelf sat a couple of dusty old jam jars containing screws and nails.

“Look,” said Tom, “there’s a mouse skeleton on the floor. Manu would love that for his collection.”

“We can give it to him as a present,” said Jasmine. Her six-year-old brother, Manu, kept a gruesome collection of animal bones and skulls in his bedroom. “But we won’t tell him where we got it. This clubhouse is our secret.”

“That shelf will be perfect for books,” said Tom. “And we can put our maps of the rescue centre up on the wall.”

It was a Friday afternoon in late October and they had a two-week half term holiday stretching out in front of them. Jasmine and Tom were planning to run an animal rescue centre when they grew up, and their new clubhouse was where they were going to work out all the details.

“What shall we call the club?” asked Jasmine.

“The Animal Rescue Club,” said Tom.

Jasmine screwed up her nose. “Not very original.” Then her eyes lit up. “Oh, but it’s A.R.C. for short! Arc. Like Noah’s Ark.”

“Exactly,” said Tom. “So it’s where abandoned animals come to be safe. Like you, Sky.”

He reached down to stroke Sky’s silky fur, and Sky wagged his feathery tail across the floor.

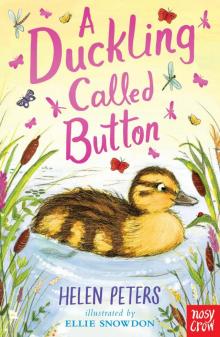

Four months ago, Jasmine had found Sky abandoned and left to die in a hedge. She had nursed him back to health and now he was completely devoted to her. Jasmine and Tom had also rescued a clutch of orphaned duck eggs from the riverbank in the spring, after a dog had killed the mother duck. The surviving duckling, Button, was now a fully-grown drake, who lived happily with the free-range chickens. And Jasmine’s very first rescue animal had been a tiny runt piglet that she had found on a neighbouring farm. She had called the piglet Truffle, and the sick little runt had turned into a giant sow, who lived in the orchard behind the farmhouse.

“I’m not allowed to keep any more animals,” said Jasmine. “Mum and Dad made me promise that if I rescue any more, I have to rehome them.”

“Will you still be able to look after my guinea pigs at Christmas?” asked Tom.

“Of course I will,” said Jasmine. “Are you going to your granny’s in Cornwall again?”

“Yes,” said Tom. “It’s going to be great. She makes the best Christmas dinner ever. And we’re going to swim in the sea on Christmas morning.”

“Swim in the sea? On Christmas Day?” said Jasmine. “Are you crazy?”

Tom was about to reply when something thudded against the door. Then came frantic scratching on the wood and an ear-piercing yowl.

The children looked at each other in alarm.

“Sounds like a cat,” whispered Jasmine.

“A really angry cat,” said Tom.

“Maybe it’s a wild cat,” said Jasmine, “and it’s been living in this shed. And now we’ve shut the door and it can’t get in.”

The cat continued to yowl and scratch at the door.

“We could tame it and have it as our club mascot,” said Tom. “If it’s living here, it kind of belongs to the club anyway.”

“That’s a brilliant idea,” said Jasmine. “And I wouldn’t be keeping an animal, because this is its home already.”

“I wonder what it looks like,” said Tom.

They tried to peer through the cracks in the door, but the gaps were too narrow and they couldn’t see the cat.

“We need to let it in,” said Jasmine, “if it lives here.”

“We’d better stand well back,” said Tom.

“I don’t think it will hurt us. It’s probably just confused because the door’s shut.”

Tom looked doubtful. “I don’t know. It sounds really fierce.”

“It’ll be fine,” said Jasmine confidently. She pushed the door open.

Into the shed shot a screaming bundle of grey fur. It hurled itself at Jasmine, hissing and spitting. She screamed and covered her face with her hands as the cat leapt up at her, scratching and biting. Jasmine screeched in pain and, with a final terrific yowling, the cat sprang down and bolted out of the shed.

“Are you all right?” asked Tom, sounding shaken.

Jasmine sat heavily on the collapsing bale behind her. She looked at her hands. They had deep red scratches all along them, and there were sharp teeth marks on her right hand.

“That must really hurt,” said Tom.

Jasmine clutched her hands together to try to stop the pain. “That cat really didn’t want us to be here. Ow, my hands sting so much.”

“You need to run them under the tap,” said Tom. “Let’s go indoors.”

Jasmine frowned. “What was that?”

“What?”

“That funny squeaking sound.”

“I didn’t hear anything.”

“Listen,” said Jasmine.

They listened. Birds tweeted in the garden. Sheep baaed in the field. From the orchard came Truffle’s low contented grunt.

“I can’t hear anything,” said Tom. “Let’s go.”

They stepped out into the sunny garden, avoiding the prickly leaves of the holly bush beside the shed. Then Jasmine heard it again: a high-pitched sound, somewhere between squeaking and mewing.

She turned to Tom. His expression showed her that he had heard it too.

“What is it?” he whispered.

“I don’t know,” said Jasmine, “but there’s something in there.”

They crept back into the half-light of the shed. There was another squeaking sound.

“It’s coming from behind that bale,” said Tom.

The baler twine that had held the straw together had broken, so that much of the straw had collapsed in a messy heap. The children peered over the bale into the dark corner.

Jasmine gasped in delight. “Kittens!” she whispered. “Oh, they’re so cute!”

“Three of them,” said Tom, grinning with excitement. “They’re tiny.”

The kittens were cuddled up together in a deep nest of straw. One was a tabby, one was ginger and the third was black. The tabby kitten and the ginger one lay still, but the black kitten was crawling over its littermates, mewing. “They’re gorgeous,” said Jasmine. “I wonder how old they are.”

“They can’t be newborn,” said Tom, “because their eyes are open.”

“So they must be at least a week old. I don’t think they’re much older than that. They’re so little.”

The black kitten gave another piercing mew.

“It wants its mother,” said Tom. And then he drew in his breath and looked at Jasmine in horror.

“Oh no,” said Jasmine. “That cat. She must be their mother.”

“We shut her out from her kittens,” said Tom. “And now we’ve frightened her away.”

“That’s why she was so fierce,” said Jasmine. “She thought we were threatening her babies.”

“We need to get her back,” said Tom. “If she can’t feed the kittens, they’ll die.”

They walked out into the garden, looking for the cat. But there was no sign of her.

“How are we going to get her back?” said Tom. “She’s completely wild. She’s not going to come if we call her, is she?”

Jasmine thought for a second. Then she said, “Food. All animals come for food. And she must be really hungry if she’s feeding kittens.”

They ran up the garden path and in through the back door of the farmhouse to the scullery. Jasmine had two cats of her own, Toffee and Marmite, and their food was kept in the cupboard next to the sink. She grabbed two pouches from the box and some empty takeaway containers from the next cupboard.

“We’ll use these as bowls,” she said. “We can lay a trail of food across the garden, leading up to the shed. That should tempt her back.”

In the garden, Jasmine tore the top off the first pouch and started squeezing it into a container.

“Don’t put too much in each one,” said Tom, “or she’ll be full before she gets to the shed.”

They put a little food in each container and laid them in a line from the bottom of the garden to the shed. Then they tiptoed in to look at the kittens. The black kitten was still mewing piteously.

“Do you think we should give them some milk?” asked Tom.

“Kittens can’t have cows’ milk,” said Jasmine. “It upsets their stomachs. I wish Mum or Dad was here. They’d know what to do.”

Jasmine’s dad was a farmer and her mum was a vet. Dad was out in the fields feeding his calves and Mum was working at the vet’s surgery.

“You could phone the surgery,” said Tom. “Even if your mum can’t speak to you, one of the nurses would know what to do, wouldn’t they?”

“Good idea,” said Jasmine. “Let’s do that now.”

“Should I stay here,” Tom asked, “and keep an eye on the kittens?”

“They should be OK for a bit. And the mother won’t come back if we’re here. We should leave them alone so she feels safe to return.”

“Hopefully she’ll smell the food,” said Tom, “and she won’t be able to resist.”

“What did Linda say?” asked Tom, when Jasmine put the phone down. Linda was the head nurse at Mum’s surgery.

“Well, we need to take away the food bowls near the shed,” said Jasmine. “Come on.”

“Why?” asked Tom, as they ran down the garden path.

“She said it’s good to leave food out, but it should be at least three metres from the nest. The mother won’t go back to the kittens if there’s food nearby, because she won’t want to attract other cats to her nest.”

Tom picked up the food bowl in the shed. “And what about the kittens?” he asked.

Jasmine took the bowl they had left outside the door. “Linda said we should leave them. Their mother has to go off hunting, so they’re used to being alone for short periods. And they can survive for several hours as long as they’re warm and dry.”

Tom looked worried. “But the mother was probably coming back from hunting when we scared her away. She might already have been out for hours.”

Jasmine stared at him anxiously. “I hadn’t thought of that.”

“So what should we do?” asked Tom.

“I don’t know. We definitely shouldn’t touch them. The mother won’t like it if there’s a strange scent on them. Linda said she might move them anyway now, since we’ve disturbed her nesting place.” Jasmine looked at Tom and saw that he felt as guilty as she did.

“But what if she doesn’t come back?” asked Tom. “They won’t survive on their own for much longer.”

“Linda said we should watch from a distance to see if she comes. Let’s get a rug and wait on the other side of the garden.”

“And if she doesn’t come?” said Tom.

“I don’t know. But I’m sure she will. They’re her babies, after all. She’s bound to come back.”

Jasmine tried to sound confident, but inside she felt horribly worried. What if the mother cat never returned? Then she and Tom would be responsible for orphaning three tiny kittens, not to mention causing terrible distress to the poor mother.

They fetched a rug from the cupboard under the stairs and sat by the hedge on the other side of the garden. They waited for what seemed like hours. As dusk fell, the colours of the garden faded and the world began to turn to shades of grey.

“I’m freezing,” Jasmine whispered.

“Me too,” said Tom. “I wish I had gloves.”

Jasmine thought about going inside to fetch gloves and a warmer coat, but she was afraid to move in case the cat was nearby and she accidentally frightened her away again.

Why wasn’t Mum home from work yet? Jasmine checked her watch and was amazed to find that only twenty-five minutes had passed since they had sat down.

Then Tom nudged her. “Look,” he whispered.

Slinking silently through the shadows by the hedge was the mother cat. She slipped inside the shed.

Jasmine felt her shoulders drop with relief, and realised that she must have been hunching them all this time.

“Phew,” said Tom. “I was so worried. Those poor kittens must be so hungry. I bet they’re pleased to see her.” He stood up and rubbed his hands together. “I’m freezing. Let’s go in.”

But Jasmine was still watching the shed. “Wait,” she said.

“Why?”

“Remember what Linda said? The mother might take them away.”

Tom frowned. “She wouldn’t really, would she?”

But he turned to look at the shed. And at that moment, the cat came padding out through the doorway, carrying a kitten in her mouth.

“Oh, no,” said Jasmine. “She is moving them.”

“We should follow her,” murmured Tom. “See where she goes. Come on.”

Jasmine grabbed the hem of his coat. “No,” she whispered. “We might scare her even further away. And she might not come back for the others if she knows we’re nearby. Let’s just watch from here.”

Tom sat down. They watched the cat as she slunk back along the hedgerow. Near the bottom of the garden, she disappeared behind a bush. They kept looking but she didn’t reappear.

“She’s gone through the hedge into the fields,” said Tom. “She might be going miles away.”

“She’s got to come back for the other two, though,” said Jasmine.

“How about when she comes back for the next one, we just creep down the garden on this side?” said Tom. “She won’t see us from over there, and we might find out where she’s going.”

So when the cat padded back a few minutes later and fetched the second kitten, Tom and Jasmine stood up very quietly and crept down their side of the garden, keeping pace with her. When she disappeared behind the bush again, they moved slightly further down, so they would see her come out on the other side.

The cat emerged from behind the bush and padded on towards the bottom of the garden, the kitten dangling from her mouth by the scruff of its neck. When she reached the hedge, she didn’t take her kitten through it, as they had feared she would. Instead, she made for the rickety old wooden tool shed in the far corner of the garden. The door was shut, but there was a gap at the bottom of the wall where one of the planks had rotted away. The cat squeezed through the gap and disappeared into the shed.

Jasmine grinned at Tom. “That’s perfect!” she whispered. “She’s stayed in the garden!”

Tom looked excited. �

�We can leave food out for her, and then she’ll grow tame, and we’ll be able to play with the kittens.”

“Jasmine, Tom, are you out there?” called Jasmine’s mum from the top of the garden.

“Quick,” whispered Jasmine, “before she shouts again and scares the cat away.”

“There you are,” said Mum, as they ran up the path. “What are you doing out here without coats on? You must be frozen. Come in for dinner. It’s all ready.”

“We have to stay out a little bit longer,” said Jasmine. “It’s an emergency.” And she quickly told her mother the whole story.

“Well, it sounds as though everything’s fine,” said Mum. “The cat’s moving her kittens to a safe place.”

“But she hasn’t moved the third kitten yet. We need to make sure she comes back for it.”

“There’s no reason to suppose she won’t,” said Mum. “You can check after dinner. Dad’s made spaghetti bolognese.”

The mention of her favourite dinner reminded Jasmine how cold and hungry she was. She and Tom followed Mum up the path.

“We’ll come out straight afterwards,” said Jasmine, “and check she’s taken the third kitten.”

“And if she has,” said Tom, “we can start sorting out the clubhouse.”

“Two whole weeks of holidays,” said Jasmine. “We can make the clubhouse amazing.”

In the farmhouse kitchen, Dad was serving out the dinner. Manu and his best friend, Ben, were sitting at the table, sucking spaghetti noisily into their mouths. Jasmine’s sixteen-year-old sister, Ella, was also there, a book propped open in front of her.

“How was your school outing, boys?” asked Mum. Manu’s class had spent the day at a local museum, learning about the King Charles the Second.

Manu grinned. “It was so cool,” he said. “We saw a dead fox on the road. It was all squashed in the middle where a car had run over it.”

“Ugh,” said Jasmine. “That’s disgusting.”

Jasmine Green Rescues A Duckling Called Button

Jasmine Green Rescues A Duckling Called Button A Piglet Called Truffle

A Piglet Called Truffle A Deer Called Dotty

A Deer Called Dotty An Owl Called Star

An Owl Called Star Anna At War

Anna At War The Secret Hen House Theatre

The Secret Hen House Theatre A Lamb Called Lucky

A Lamb Called Lucky The Farm Beneath the Water

The Farm Beneath the Water A Kitten Called Holly

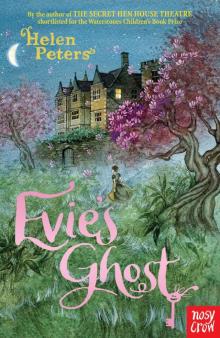

A Kitten Called Holly Evie's Ghost

Evie's Ghost A Duckling Called Button

A Duckling Called Button